Levent Akbulut explores the cultural significance of observing anniversaries and touches on their potential to build a strong social and political movement.

Anniversaries and symbolic dates are a great way to build a sense of self-awareness as a cause or movement and to highlight the significance of events in history.

This year is of particular importance in the drug policy reform and anti-prohibitionist movements.

Fifty years ago, member states of the United Nations signed the

Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961). The convention was very much born out of the values of the American temperance movement of earlier decades and the increasing globalisation of American culture in the years following the Second World War. These phenomena owe their relevance to the growth of the United States as a major world power, and while more recently America has slowly been losing its iron grip on the internal politics of dependent territories, for the last fifty years the drug war has been a trademark of US hegemony in the international arena.

This year is also the 40th anniversary of when Richard Nixon symbolically called for a

war on public enemy number 1, drugs. As the narrative goes, the drug war is supposedly fought to protect young people, or perhaps more likely the progeny of the socio-economically advantaged. This is the case although the availability of drugs is still neither controlled or restricted, rather the policy inevitably leads to a shift in scenarios where the youth get exposed to gang culture or have to consider the underground drugs trade as a career path. Richard Nixon almost certainly had the young long haired anti-war protestors sitting in front of the White house lawn in mind when he ignored the findings of the

Shafer Commission and chose to push for a tougher line on the idealistic pot smoking youngsters.

Just weeks before Nixon made this declaration, the United Nations tightened the

first convention and the UK’s own

Misuse of Drugs act achieved Royal assent and became law. This is the Act of Parliament that is supposed to classify drugs based on relative harms but suggests cannabis is more harmful than ketamine and that ecstasy is on a similar level of harm to cocaine and heroin while excluding alcohol and tobacco from classification. So symbolically powerful is this unholy trinity of drug war anniversaries, the drug policy reform movement has made this a major theme of the work we do this year and was even adopted by ourselves as the narrative for Students for Sensible Drug Policy UK’s second annual conference where we invited students from all over Europe to attend and share their experiences as reformers.

As we in the UK enjoy the holidays of the next couple of weeks, some remembering or celebrating events of spiritual and cultural significance, others are just spending this time with friends and family. It is worth knowing that there were three dates this last week of significance for the student drug policy reform movement in the UK and especially to the youth culture for which our group seeks to provide representation.

Out of America’s cannabis obsessed war on drug users,

420 day has become a symbol of youthful rebellion against a pointlessly punitive prohibition. For some reason or another, North American cannabis culture has adopted the 20th of April and specifically at 4:20pm as a time to celebrate the consumption of the flowers of the cannabis plant.

Rumour has it the term was originally coined by a group of teenagers in San Rafael, California who used to meet at 4:20pm to go on an expedition to find an abandoned cannabis crop that they heard about. Since then, 4:20 evolved into a codeword that they used to refer to cannabis smoking generally and has gained wider social use in the English speaking world, though most notably in North America. It should be noted that different groups make different claims on the origin of the significance of the number.

Some North Americans even ritualise their use of cannabis to not start sooner than 4:20pm each day. Most significantly it refers to what is now a counterculture holiday which in many cases has a political message such as to call for the decriminalisation or legal regulation of cannabis. Why cannabis has such a culture is worth further discussion but not for this blogpost.

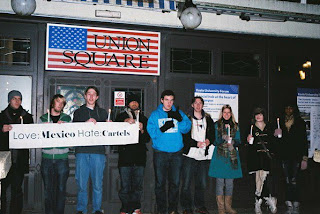

The date has increasingly been adopted to organise such politically motivated gatherings in the United Kingdom. The forerunners of Students for Sensible Drug Policy UK organised a 420 day rally in Leeds back in 2008, just days after voting to form Students for Sensible Drug Policy UK. This year a few of our members from London and the South East took to Hyde Park in London for the 420 day celebrations and handed out literature about our movement as well as stickers

and bustcards.

I gave a speech on why young people should become activists just after

Peter Reynolds, the leader of the newly formed

Cannabis Law Reform party, Clear, called on the people to become politically motivated. Independent activist, Ed Green then gave a brief background on the historical origins of cannabis prohibition.

The event was very peaceful, we were able to engage a lot of young people and everyone seemed to be having a good time. Just as we were entering the evening, some kids who seemed to be in rival gangs started throwing around glass bottles and attacking each other. One even narrowly missed my head. The violence scared a lot of the young people and you could see a swarm of heads standing up and running to leave the park, despite the pleas of their peers for the fighting to stop the few troublemakers carried on hurting each other until the police arrived.

Some have said that I should not be mentioning these incidents which took place towards the end of what was a very successful and peaceful event, but lest we forget that it is our drug laws and our social policies that have encouraged the growth of this youth gang culture. 420 day need not have lost its political and social significance as a creative reaction against cannabis prohibition.

The day earlier, the 19th of April is observed by an even smaller subculture, the psychedelic movement as “Bicycle day”. Legend has it on the 19th of April 1943, Swiss chemist,

Albert Hoffman, deliberately ingested 250 micrograms of LSD. Three days earlier he noticed marked psychoactive changes while handling the substance. His intention was to predict a threshold dose. An hour later he experienced sudden and intense changes in perception. He asked his laboratory assistant to take him home. Due to wartime restrictions that prevented driving with motor vehicles, they took a bicycle home. He later wrote of his experience with LSD:

"... little by little I could begin to enjoy the unprecedented colours and plays of shapes that persisted behind my closed eyes. Kaleidoscopic, fantastic images surged in on me, alternating, variegated, opening and then closing themselves in circles and spirals, exploding in colored fountains, rearranging and hybridizing themselves in constant flux ..."

The events of the day, now known as ‘Bicycle day’ proved to Hoffman that he had made a significant discovery. This date is remembered by some people in the psychedelic subcultures, including music scenes. While official events are rarely called for, invitations to observe the event now get sent out on Facebook.

These dates are not just a reaction against the cultures we live in but exist due to the social settings that these subcultures exist within. The parallel with the drug war anniversaries lies in the reasons that they hold significance. They represent important dates in the social ritual consumption of certain prohibited substances, while these drug war anniversaries remind us of the absurd and always socially ruinous policies that seek to legislate otherwise victimless human behaviour and criminalising those the worst affected.

The 18th of April 2008 was the date a small group of student cannabis law reform activists at the University of Leeds voted to form

Students for Sensible Drug Policy UK.

For years we had wondered why there were campaigns to join covering almost every social problem, but none to talk about how harmful our prohibitionist drug policies had become. Yet the constituent members of the National Union of Students would quite happily regularly celebrate the consumption of alcohol, one of the more toxic of the commonly used recreational drugs while ignoring the social and health harms caused by our current drug policies. This year in 2011, the NUS lost it’s battle to stop the government trebling top up fees from £3K a year to £9K. At NUS annual conference this year, no one was quite sure what the next step was but they all pledged to carry on. This year we are many more in number and more confident on the campuses where we organise.

These holidays when you sit down for dinner with friends and family, or whether you just use the extra time to study, remember this week as the start of a UK youth and student movement for drug policy reform. This week might even be the week you decided to get involved and become an activist...

You can start a local group of Students for Sensible Drug Policy UK at your university or college or even in your local community. Contact us through the

chapter start up form on our website for more information on getting involved.